ROBERT INDIANA

ROBERT INDIANA

Book of Love (R,B,G), 1996 | G30581

26 X 26 X 2 inches

Enamel on aluminum

Robert Indiana | was born in New Castle, Indiana on September 13, 1928. He was adopted as an infant by Earl Clark and Carmen Watters Clark and named Robert Earl Clark. Robert Clark would legally change his name to Robert Indiana in 1958, assuming what he called his “nom de brush” and acknowledging his roots inthe American Midwest. Indiana grew up in a financially unstable home. During Indiana’s early childhood hisfather, Earl Clark, held a variety of odd jobs from executive positions to pumping gas at an oil station. Earl’sinability to hold a steady job was a source of constant stress at home and when Indiana was nine years old his parents divorced. After the separation, Carmen Clark went to work as a waitress at a local diner and Indianamoved-in to live full time with her. This move would prove to be influential to Indiana's artistic career later-on inlife.

The early 1900’s saw the development of youth movements that grew as a countercultural reaction to industrialization in Germany. During the first several decades of the 20th century, these beliefs were introduced to the United States. The movements rejected the rapid trend toward urbanization, emphasized nature and a yearning for spiritual life. In turn many young Americans adopted the back-to-nature beliefs and practices of thenew immigrants, even opening in 1934 the first health food store in Santa Barbara, California.

By 1937 Carmen would have been influenced by the new non-conformist culture and lifestyles many young Americans were practicing. Carmen was known to be a free spirit and enjoyed the freedom of an alternative lifestyle and frequently moving to a new location. By the age of seventeen, Indiana had lived in twenty-onedifferent locations.

Graduating high school in 1946, Indiana enlisted in the U.S. Air Force, intending to fund his college studies through the G.I. Bill. In 1949, with his service complete, he enrolled at the Art Institute of Chicago. Indiana also studied at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine. He graduated in 1953 earning aB.F.A and a fellowship to study art in Edinburgh College of Art in Scotland. Upon his return to the United States in1954, he settled in New York. Although Indiana originally planned to settle in Chicago upon his return from Europe in 1954, his lack of funds kept him in New York.

Two years after moving to New York his job at an art supply store led to a fortuitous 1956 meeting with the artistEllsworth Kelly. Kelly had entered the store to purchase a postcard that Indiana had used in a window display. The two became romantically involved and Kelly both encouraged him to move to the Coenties Slip area of lowerManhattan. On Kelly’s advice, Indiana took up residence in Coenties Slip which was once a major port on the southeast tip of Manhattan. There, he joined a community of artists that would come to include Ellsworth Kelly, Agnes Martin, James Rosenquist, and Jack Youngerman. The move, which brought him into a community of artists, proved highly influential to Indiana's later style of images combining stenciled text, numbers and hard-edged bright color field paintings.

Indiana began the Confederacy series of paintings in 1961 as the American south exploded with violence in the early1960s with the start of the Civil Rights movement. Indiana’s new series of paintings were visually bold withelements of graphic design and the dynamics of American advertising. However, each series of works were thematically devoted to former slave-holding states like Alabama and Mississippi. The paintings of the Confederacy series show a map of a southern state encased in multiple circles and are displayed much like a dart board. In the rings, Indiana stenciled a caption: “Just as in the anatomy of man, every nation must have its hindpart.”.

Words and numbers became prominent in Indiana's work. While his graphic style and use of popular words and images were similar to the style of the new Pop art movement, Indiana distinguished himself through the autobiographical nature of his work. Indiana always created art that overtly addressed contemporary political and social themes, such as the struggle for Civil Rights. Furthermore, unlike his Pop art leading contemporaries, Indiana didn’t embrace consumerism. In fact, he was critical of the consumer and political excesses of American pop culture.

Along with the Civil Rights Movement and the New Left, the Hippie movement was one of three dissenting groups of the 1960s counterculture. Hippies rejected established institutions, criticized middle class values,opposed nuclear weapons and the Vietnam War. Instead, hippies championed sexual liberation, embraced aspects of Eastern philosophy and were often vegetarian and eco-friendly. They also promoted the use of mind-altering drugs and enjoyed the freedom of their communal lifestyle.

Indiana had been introduced to this type of alternative lifestyle as a child while growing up with his free-spiritedmother in the early 1940’s. Even though, the Hippie counterculture didn’t become popular until the 1960’s, hippies inherited a tradition of cultural dissent from their previous generation who were deeply influenced by earlyAmerican immigrants of the late 1930’s.

Indiana’s popular LOVE design first appeared in the painting titled 4-Star Love in 1961. He later recreated the design in many other media, transforming it into hard-edged color variations on canvas and cast in sculptures. Then, in 1965 it was selected by The Museum of Modern Art for its Christmas card. The MoMA Christmas card publicity led Indiana to his first exhibition of LOVE works in 1966 at the Stable Gallery. Theexhibit featured the word itself, stacked in two rows with the "O" slightly tilted. While simple, the word made apowerful statement at a time of national and international unrest. In America, Indiana’s LOVE had countercultural implications as America intensified its campaign in Vietnam. For many Americans in the antiwar movement, the words “love” and “peace” became interchangeable. Furthermore, the universalinvocation of the word itself had a particular resonance with the public coming from a gay man in the yearsbefore Stonewall. Indiana’s LOVE image popularity emphasized its great resonance with large and diverse audiences. LOVE had become an icon of modern art even appearing on a commemorative U.S. Postal Servicestamp issued on Valentine’s Day, February 14, 1973. Indiana’s LOVE was universally adopted as an emblemof the “Love” Generation, and this is evidenced by its subsequent translations into AHAVA (Hebrew) and AMOR(Spanish).

LOVE proved a source of inspiration even for John Lennon, who while viewing Indiana’s LOVE exhibit, responded to a comment that love was surrounding him by replying "All you need is love." This statement would amplify Indiana's message, becoming the title for the Beatle's hit song in 1967 and an indelible and still-popularslogan.

In 1973 Indiana purchased a mansard Victorian-style home in the island of Vinalhaven, Maine to use as aseasonal art studio. The property was named The Star of Hope. Indiana had envisioned turning the Star of Hopeinto a museum dedicated to his life and work. In 1978 Indiana moved into the property to live full-time. Indiana’scareer went into a lull after his move to Vinallhaven. Then in 1999, the Morgan Art Foundation took up thecause of re- energizing Indiana’s career and offered to rebuild his market. That same year, Indiana granted the Morgan Art Foundation retroactive copyright and trademark rights to his LOVE designs produced between1960 and 2004.

Indiana, eventually began to seek new partnerships and in 2008 he revisited his iconic LOVE work by recasting the sculpture as another four-letter word, HOPE in support of Barrack Obama. Obama used the word as one of his slogans for his 2008 U.S. presidential campaign. The new HOPE sculpture was unveiled onAugust 25, 2008, at the Democratic National Convention in Denver, Colorado. This time Indiana partnered withMichael McKenzie of American Image Art to promote his artwork and formalized this relationship with a contractthat authorized American Art Image to produce all sculptures and prints based on HOPE. Indiana’s legacy, theLOVE and HOPE designs, have since been reproduced on countless products. His work reflects on contemporary issues of its own time. However, Indiana’s LOVE and HOPE carry a deeper personal and universal message to future generations of timeless human values. Proud to be "a people's painter,” Indianaonce argued against applying copyright to a LOVE poster created to promote his own art opening at the StableGallery. Indiana even declined the copyright of LOVE on a Christmas card for MoMA because he didn’t likethe way the copyright symbol looked on his art.

When asked about his LOVE series Indiana said, “oddly enough, I wasn’t thinking at all about anticipating thelove generation and hippies. It was a spiritual concept. It isn’t a sculpture of love any longer. It’s become the verytheme of love itself.”

Indiana’s estate was estimated at 77 million dollars at the time of his death. A day before his death theMorgan Art Foundation filed a federal lawsuit against Indiana accusing him of breach of contract.

Robert Indiana died of respiratory failure on May 19, 2018 at his home: Star of Hope.

ARTIST COLLECTIONS

-

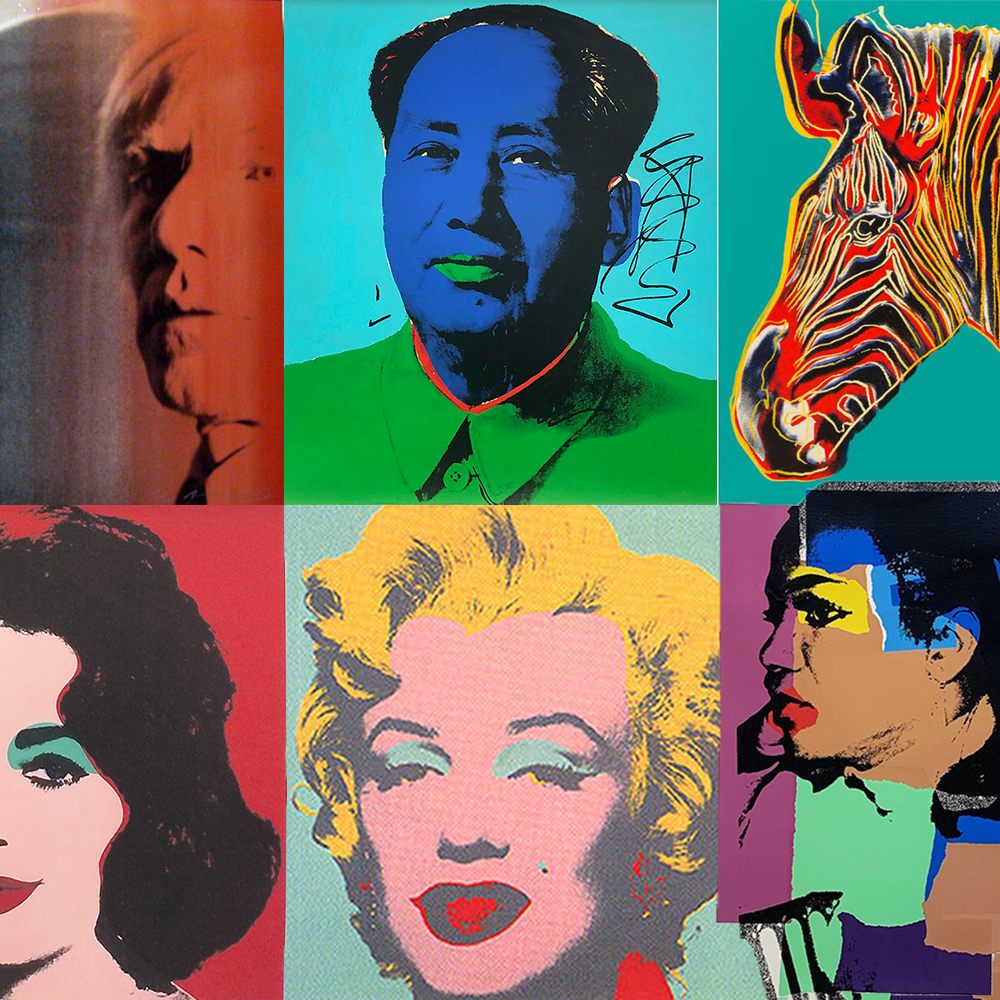

ANDY WARHOL ART

WARHOL | Biography